Traditional school disciplinary strategies are guilty – guilty of being woefully ineffective and failing kids and educators alike. They aren’t needed for most of the students in our schools, and in a sad irony, they don’t work for the students to whom they are most applied! Research has clearly shown that disciplinary actions actually increase the likelihood of further discipline and are related to higher drop-out rates as well as lower academic achievement and even eventual juvenile justice involvement (APA, 2008).

Despite having learned a lot about the brain in the last few decades, school discipline hasn’t changed much. Sure, we have fancier jargon for describing these strategies, but the basic ideas and interventions are the same. Time-out, detention, suspension, expulsion are all aimed at motivating students to behave better – which ought to work if a lack of motivation is the reason kids are behaving poorly in the first place. But, as I’ve explained in previous blogs, thanks to research in the neurosciences we now know that this conventional wisdom about challenging behavior is flat out wrong. Students who struggle to control their behavior at school don’t lack the will to behave well, they lack the skills to behave well — skills like flexibility, frustration tolerance and problem-solving. No end of motivational strategies will teach students neurocognitive skills like these that are the reason they are struggling in the first place. I’ve also discussed in previous blogs some of the dangerous side effects to the ineffective disciplinary strategies we use in schools.

As if all this wasn’t enough, guess who suffers the most from traditional school discipline? The most at-risk, misunderstood and marginalized students, specifically students of color and students with histories of trauma and exposure to chronic stress. Students of color, particularly African-American students, are suspended at disproportionate rates and are on the receiving end of much more severe punishments than their white peers for far less serious behavior (Gilbert & Gay, 1985; Weinstein, Tomlinson-Clarke, & Curran, 2004). They are also punished for more subjective offenses because of something called implicit bias. Caucasian adults are much more likely to perceive the behavior of students of color as angry or threatening. It is absolutely imperative that we implement new approaches to school discipline that address these racially-biased misinterpretations of behavior. Fortunately, we are finding that when we teach school staff how to focus on a specific student’s struggles with certain skills as the root of their misbehavior, they are less likely to rely on things like race and socioeconomic status in judging students. In other words, focusing on skill, not will, has the potential to reduce the harmful effects of racial or socioeconomic disparities in school disciplinary practices.

Our schools aspire to be “trauma-informed” or “trauma-sensitive.” Many educators are being trained to understand the impact of chronic stress or trauma on students’ development, behavior, and learning. Educators have far more empathy for how chronic stress and trauma delays brain development, causing lags in skill development which result further downstream in challenging behavior at school. However, these same schools often then rely heavily on punitive school disciplinary strategies for these very students. And let’s be honest here: traditional school discipline is about as trauma-uninformed as it gets! Nowhere in the trauma-informed practice literature have I seen anyone advocating for the use of power and control to manipulate a student’s behavior. Using behavior charts and rewards and consequences is doing just that. Students who exhibit challenging behavior are often the students with trauma histories for whom these interventions not only don’t work, they do damage and make matters worse.

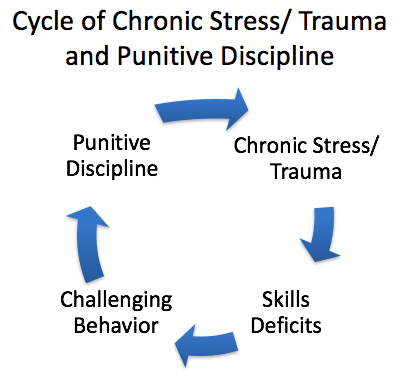

We have referred to this as the vicious cycle of chronic stress and punitive discipline (Ablon & Pollastri, 2018). Punitive discipline adds more chronic stress which further delays skill development resulting in escalating behavior which is then often met by raising the stakes with even more punitive discipline. Systems of escalating consequences are sometimes called “progressive discipline.” When it comes to curbing challenging behavior, those systems are anything but progressive. In fact, I like to refer to them as progressive dysregulation where both the student and the educators become increasingly dysregulated dealing with one another which leads nowhere good. In fact, is has been well documented that dealing with challenging behavior in the classroom is one of the biggest sources of stress for educators which drives talented, young teachers out of the profession just when we need them most.

What’s the good news here? We have the power to interrupt the cycle of chronic stress and trauma. Proven alternatives exist. Instead of adding stress resulting in further delaying skills and escalating behavior, we can buffer stress, build skills and reduce challenging behavior. These alternatives don’t rely on power and control and are restorative rather than punitive. And they are inclusive alternatives that combat, rather than reinforce, racially biased practices.

Schools represent a remarkable opportunity to help our most vulnerable kids. Where else do we have kids the majority of their waking hours, the majority of their youth surrounded by trained, professionals whose goal is to teach them? So, let’s harness that opportunity and bring school discipline into the 21st century. We need a call to action. It is high time we fix school discipline.

References

Ablon, J.S., Is School Discipline Guilty? (2018). PsychologyToday.com.

Ablon, J.S., & Pollastri, A.R, The School Discipline Fix. (2018). Norton: New York, NY.

American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. The American Psychologist, 63(9), 852.

Gilbert, S. E., & Gay, G. (1985). Improving the success in school of poor black children. Phi Delta Kappan, 67(2), 133-37.

Weinstein, C. S., Tomlinson-Clarke, S., & Curran, M. (2004). Toward a conception of culturally responsive classroom management. Journal of teacher education, 55(1), 25-38.

Learn more behavior management tips at our 2023 BEHAVE! Conference

June 12th | Education Service Center Region 13

Sara Ploof is the Marketing Project Coordinator at ESC Region 13.

Add comment